- Home

- Richard Rawlings

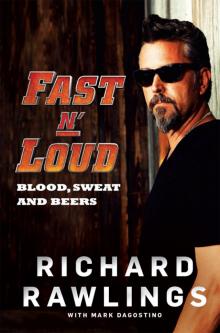

Fast N' Loud Page 2

Fast N' Loud Read online

Page 2

I wouldn’t say we were on the super-poor side, but despite all of his hard work we grew up kind of below average. We rarely had anything “extra.” He couldn’t go out and buy us the latest toys and electronics when they first came out. We couldn’t go out to nice restaurants or buy the nicest clothes. We were lucky to have what we had, and the biggest thing we had is what I would consider a normal house with three bedrooms and two bathrooms in a lower-to-middle-class Fort Worth neighborhood. My dad took real pride in absolutely every part of it, too. He mowed the lawn perfectly, and even edged the grass all around the yard. We kept a clean house. We even helped him keep the garage immaculate. I suppose that rubbed off on me, too. To this day I take great pride in everything I’m fortunate and lucky enough to own because I saw him take pride in, care for, and maintain whatever it was he was able to purchase and keep for his family back then.

That included his cars. My dad had a hankering for cars from the start, and I think that was really the only area where he would treat himself to a little something special. Some of my earliest memories are from right out in the driveway with a bucket and sponge, helping him wash the fenders to keep his car all shiny.

My dad didn’t really have a lot of money to spend on cars or motorcycles, but he always had something. I mean, it wasn’t expensive. It wasn’t the best one out there. But it was his. It was his toy.

Dad wasn’t a tinkerer. He didn’t know how to get in there and fix the engines or turn a junker into a hot rod or anything. He could change the oil, and he knew what he liked as far as choosing new wheels and making it look really good. But he always had a fun car that was sort of a showpiece, something we could take out for Sunday drives, and he took care of ’em like they were another child or something.

He was so proud of those cars that he tried to get them into car shows forever. But they were never quite up to snuff. That is, until he purchased a ’65 Mustang 2+2, maroon with black interior.

Someone else must’ve dropped out at the last minute or something, because the night before the big Autorama show at Market Hall in Dallas, they called him up and said, “Hey, you’re in. But you’ve got to load in first thing in the morning.”

We didn’t have a truck or a trailer to haul that Mustang in, so we had to drive the car to the show in the pouring rain. As soon as we were in the arena my job was to take a one-gallon bucket and run back and forth from the bathroom so he could rinse off a rag and keep wiping the car down over and over until the water spots were off of it and it looked just right.

It’s funny looking back on it, because I don’t remember a lot of the specifics about the other cars he had. I don’t remember much about the specific motorcycles, either, yet I know he had a few. Maybe my lack of memory is because he never let me touch them on my own. Hell, he would yell at me if I rode my bike between his cars in the driveway, afraid that I’d scratch one of ’em with the handlebars or something. I know now what he was really worried about: he knew that he didn’t have the money to get it fixed if something like that happened.

I do remember he had a custom truck back in the seventies, with the shag carpet and a bed in the back, and he would take his shoes off and make us take our shoes off before any of us got in it. He was passionate and strict about all of his vehicles. Hell, he was passionate and strict about lots of things, including discipline. He was quick to the belt when we got out of line, and as you can probably guess from my personality, I was the type who got into all kinds of trouble every chance I got. So I got to know his belt pretty well.

My dad was a kick, too, though. He’d do some crazy things. Like one time when the school was throwing a fund-raising fair, he rode his motorcycle up there with his leather jacket on and opened up a kissing booth. Everybody else baked cookies and sold their kids’ hand-drawn art and clay ashtrays, and there’s my dad, like, “Where’s all the moms at? One dollar per kiss!” People in Fort Worth still talk about it today!

Other kids might’ve been embarrassed by my dad’s over-the-top style of doing things, but not me. I dug it. I thought he was the coolest. And you know what? He was. He set the bar high—and from the moment I hit my teenage years, I was determined to not only reach that bar but to jump right over it. It sure would take me a long time, though. I was skinny and pretty geeky and wasn’t too good with the ladies back in high school, if you can believe it. Looking back on it, I’m glad I didn’t waste my cool in high school, though. When you go to just about any high school reunion a lot of the guys that were like me—a little too thin, a little bit of a late bloomer, a little shy with the girls—they’re pretty badass now. They’ve got the good job and the hot wife and all that. And some of the jocks that were getting all the action and thought they were the s—t in high school are kind of fat and bald and not doing so well. As they say, karma is a bitch!

High school was actually pretty rough on me. I didn’t fit in well, and I certainly didn’t like it. I think mostly it was just too slow for me. The thing I tuned in to early on, though, was that the easiest way to be cool was to stack up a whole lotta cash.

I loved money. I always did. I still do! But it was in my early teenage years when I really got a hankering for wanting to make money. My own money. And it was outside of school where I seemed to get my best education.

I worked all the typical teenage jobs. I worked at the burger joint. I worked at the drugstore. I worked everywhere. But it wasn’t those jobs that taught me about making money. It was wheeling and dealing cars on the side as a hobby.

A lot of kids get a car in high school. Sometimes you’ll find a kid who sells his car and buys another one, or who buys some hunk of junk and fixes it up in his dad’s garage and starts showing off doing donuts with his girlfriend in some parking lot. I wasn’t that guy. I was something a little different.

I would estimate that I owned a series of nearly twenty cars just in high school.

From the moment I got behind the wheel, I made it my goal to trade up to something better, or to make a few changes that could make me a little money so I could go and buy a different one, just for fun.

I had a few motorcycles mixed into that twenty, too, and to me, the wheeling and dealing was almost as much fun as driving ’em. Maybe more!

In the state of Texas back then, as soon as you turned fourteen, you could get something called a hardship license. Because my dad and my stepmom both worked, I was able to get my license in order to drive to my job. That was the “hardship.” Boom! I couldn’t afford a car at that age, so I got a motorcycle license instead. Suddenly I was off and running at the age of fourteen.

My very first car was a 1976 Chevrolet Impala. My dad bought it for me shortly before I turned sixteen. Much to his surprise, I found another car I liked better not long after that Impala landed in our driveway. I went and sold it for a hefty profit and bought myself a ’74 Mercury Comet. It was sort of a piss-color green, with a green interior. For some reason, I’ve always liked green. I was hooked on it! I put the stripes on it, and new wheels, and fresh tires, and took some of the money I was making and put a big stereo into it and all that stuff. Then I suddenly realized it was worth quite a bit more than I’d paid for it.

Boom! I sold it, bought another car, and stashed a little chunk of cash away in the bank to use for the next one.

When I started all that wheeling and dealing, I found I had a knack for keeping track of money and figuring out what was profitable and what wasn’t. It was strange in a way, because in school I had always done terrible in math. Something changed in high school, though, thanks to my shop teacher, of all people.

These days, occasionally somebody will ask me, “How can you be successful in business if you weren’t very good in math?” And I say, “Well, I wasn’t very good in math at first. But then my shop teacher at Eastern Hills High School in Fort Worth would come in every day and he’d write a number on the board. And it was usually like $4.30, or $6.10, or whatever. And he’d be like, ‘You see that? That’s what I made last

night while I was sleeping, because I got a retirement account and I put money away. And that’s what you kids need to be focusing on. You get out there and you take a portion of everything you make, and you put it up.’ He drilled that into our heads.”

Besides that important lesson in saving, I wound up talking to him one day about how terrible I was at math. I said, “I just can’t get it.”

He goes, “You like money?”

“Yes, I love money,” I said.

He goes, “Well, every single math problem from this point on, whatever they tell you—eight plus four times ten, or whatever—just put a dollar sign in front of it.”

I said, “What do you mean?”

He said, “It’s just numbers. If you like money, and you can count, when they give you a math problem, put a dollar sign in front of it.”

I swear it was like a big fat lightbulb turned on over my head, just like in one of those old cartoons. From that point forward, I never had a problem. In fact, I’m so good at keeping track of the math in my business, it drives my sister nuts. Daphne has run the accounting at pretty much all of my companies through the years, and there will be times when she’ll show me the books and I’ll turn to her and say, “That’s not right. There should be like fifteen hundred more in that account.” She’ll go away and look at it and realize that something was placed in the wrong column or something. She hates admitting that I’m right, but it happens all the time! I do this with accounts I haven’t seen in months. I just keep track of it all in my head. It’s just numbers—and as long as there’s a dollar sign in front of it, I can track it.

By the time I got ready to graduate high school (which I barely did), I was already making pretty good money buying and selling cars on the side. In fact, as graduation neared, I’d already traded my way into owning one of my dream cars: a ’78 Trans Am. It was red, but otherwise it was basically the Bandit Car from Smokey and the Bandit. Black interior, a big eagle on the hood, T-top, four-speed . . . It was just bad.

I paid $4,500 for that car. That was a lot of money back then. But it was the right car for me in that moment. When I told my dad I’d found one and was fixing on buying it, he said I couldn’t have it because we couldn’t afford the insurance. I completely ignored him. I came home with it and revved that fat V-8 in the driveway. Man, was he pissed off.

“What the hell did you do?” he yelled.

“Well,” I said, “I paid cash for the car out of my own pocket, and I already bought a year’s worth of insurance. So what’s the problem?”

“Well,” he said, just shaking his head. “There’s not one.”

So there I was, all of eighteen years old, kissing high school and all of its stupid problems good-bye and driving off into the sunset in a ’78 Trans Am. I was riding high.

That’s when I witnessed something awful.

Dad and me . . . COURTESY OF RICHARD RAWLINGS.

I was getting ready to move out of the house when the grocery-store chain where my dad worked went belly-up. Just like that, he was out of a job. The economy was a mess then, too, so that chain’s retirement program failed on top of it all. After fourteen, maybe fifteen years on the job, my dad was out of work and lost all of his retirement savings in one fell swoop.

He would eventually recover. He was always a hard worker. But things got pretty scary there for a while. Seeing something like that happen to my dad made me think hard about the type of job I wanted to have in life, and how important it would be to find a career that wouldn’t just up and disappear one day. It also taught me pretty quickly that I’d better make my own way in life, and I’d better not rely on somebody else’s potentially faulty business model to provide my security and my future.

REVVED UP

Guess what company I landed a job with right out of high school?

Miller Lite.

No joke! In case you haven’t noticed, I’ve been a spokesman for Miller Lite since shortly after Fast N’ Loud hit the airwaves. It’s the only beer I drink. I keep a refrigerator full of it in the back corner of Gas Monkey Garage at all times. People see my face on Miller Lite billboards and cruising down the road on the side of Miller Lite trucks all over the place, but back then, my first job out of high school was driving a Miller Lite keg truck at night. Bars tended to be smaller in the 1980s, which meant that they didn’t have a lot of room to store extra kegs in the back. So I basically drove an emergency keg-truck route: when a bar would run out of Miller Lite, they’d call me. My pager would start beeping and I’d haul my butt over to that bar to get them a new keg.

One night I wound up delivering to a bar in West Fort Worth. It was late at night, and one of the locals who was often there, an older gentleman, started giving me a hard time.

“What are you going to do with your life?” he said. “You know you can’t drive a keg truck forever.”

I thought, You’re sittin’ in a bar, so what the hell is your problem? But what I said was, “Well, sir, my dad always told me I needed to get a good job with good benefits. So quite frankly, I’ve been thinking I might go be a police officer.”

“Well, then why aren’t you in the police academy instead of delivering beer?” he asked.

“It’s not that easy. You’ve got to be sponsored or hired by the city before they’ll let you enroll,” I told him. It was true. I’d already started looking into it. Cops make good money, drive fast cars, carry a firearm, and have just about the most secure retirement funds around. Seemed like a good deal to me.

“Well, why didn’t you say so?” he said. “I’ll sponsor you!”

I thought this guy was blowing steam, but guess what? He was the mayor of a nearby city! And he kept his bar-stool promise. Three weeks later, I was enrolled at the police academy.

Talk about a life lesson! I could’ve blown that guy off or mouthed off to him, but I didn’t. I always showed respect to my elders, just like my dad always taught me, and late one night in a random bar it paid off for me. Big-time.

I became an officer before I was twenty years old. My dad was really proud. He could hardly believe it! I had already moved out and had my own place, so I kept driving the keg truck as a way to pay my bills the whole time I was in training. Sure enough, though, I became a cop in the city of Alvarado. I didn’t stay too long. When the opportunity became available I jumped over to a slightly higher-paying job as a Tarrant County constable (which is just another form of police officer), covering the whole Fort Worth area. The police work was only part-time, though. I was making enough money to keep up my penchant for buying cool cars and motorcycles on the side, but not much else. I wanted to find full-time employment.

I thought the answer would be stepping up to a full-time cop job with a big city, and the force that everybody wanted to work for at that time was in a suburb of Dallas called Coppell. Coppell was the fastest-growing city in the area and they had four or five openings that I knew of, so I picked up an application packet and filled it out. It was a huge packet full of background-check information and everything you can think of. It took me a while to complete, but when I dropped it off, I noticed another job posting on their bulletin board. It said they were accepting applications for new firemen, too. I’d never considered becoming a fireman before, but the application packet was exactly the same as the one I’d just filled out. So I Xeroxed it and turned them both in.

Next thing I knew, I was called in for some physical tests of strength and endurance. Luckily I’d grown out of my scrawny phase. I passed with ease and I wound up landing a job as a fireman, one of four full-time, salaried spots out of probably two thousand applicants. Life is crazy, isn’t it? You just never know what’ll happen if you put yourself out there and go for it.

So I’m a fireman and a part-time cop on the side. (Since firefighters work an odd schedule of one day on, two days off, I had time on my hands.) Oh yeah, and the firefighter training they put me through included full EMT training, too, so I picked up even more work as an EMT on the side.

There I was, twenty-one years old, and I was a certified police officer, firefighter, and EMT. No more driving a keg truck for me. And talk about cool. Remember how I said I wasn’t really good with the ladies in high school? Yeah. Try putting on a uniform and see how fast your love life changes.

Having all of that success so quickly didn’t settle me down, though. In fact, it fired me up. I got antsy. I wanted to see what else I could accomplish. My head started filling up with all sorts of crazy entrepreneurial ideas, and as far as I could tell, there was nothing stopping me from pursuing any of them. So that’s what I did.

I opened up a detail shop with a buddy of mine. He knew all the ins and outs of the detail business at the time, and I knew what I liked after outfitting so many of my own cars through my high school years, so we blew it out and quickly built a following. I’d gotten lots of practice making cars look good, so I figured that was an easy way to make some additional cash on the side. The thing I found is that everything I did made me want to do even more. I developed a sensational appetite for success, and somewhere deep down, I knew that I wanted to build and do something big. Really big.

I would sit around the firehouse with the other guys and bounce things off the wall all the time. Crazy ideas for businesses and products, you know? My sister, Daphne, says I used to bring up all sorts of crazy ideas when I was younger, too, just sitting around the dinner table. I suppose I’d always had a bit of that imaginative, entrepreneurial drive in me, but this firefighting era of mine was the first brainstorming period that felt like more than a dream to me. I was positive these ideas I was tossing around were actually going to lead to something.

The older firefighters, who were all set in their ways and just waiting to retire, would laugh at me like I was some sort of dreamer and fool. I never understood that. Doesn’t everybody dream of something bigger? Something more?

Finally, one day, I came up with an idea that would prove to all the doubters that I could accomplish something nobody’d ever thought of before.

Fast N' Loud

Fast N' Loud